Duro

Duro was walking along the trough, checking to see if all the beasts were drinking properly. Not taking clear water was one of the first indications of certain illnesses. Even though Duro was not the most experienced handler, he’s been picking up on beast lore fairly quickly since he left his distant homeland three years ago. These days he was working alongside Grea and the rest of the animal handlers with sufficient confidence. Suddenly he became aware of an Ifreanni emitting a low hissing sound as it lowered its head. The small frill at its neck was opening and closing slowly. Duro stepped carefully but decisively to the horse-sized lizard’s left and drew it away by the reins, leading it to the far end of the trough while cursing under his breath. He tied the mount to a post, watching the creature’s attitude and color change immediately; its scale hue became a lighter orange and it stopped stretching its frills.

Duro disliked Ifreanni for their many inherent dangers and issues, but what he disliked much more - detested, even - were handlers who endangered their beasts and the members of the comitatus with their negligence. The muscular, lean reptiles were difficult to handle due to them being prime predators: they were prone to attacking anything smaller than themselves even after domesticated, bullied their own kind, and tended to steal things to use as decoration for their nests. In short, they were nasty, belligerent creatures. However, their great resistance to hot, arid climates, as well as their speed and incredible constitution made them extremely useful. This particular female was in heat, and as such, was inclined to be exceptionally malevolent with males. Therefore, great care should have been taken at all times to separate her from other beasts. The lad checked the lizard’s arm harness and muzzle to make sure no other mistakes were made before leaving the beast ward.

Whichever of the handlers neglected to properly take care of this Ifreanni would be severely punished - Duro knew this. It was their job to stay a little after taking them to troughs and see if they act weird. He was seething with anger when he walked up to Grea, the chief beastmaster, who was sitting by one of the seven campfires, so he had to take some time to calm himself before addressing her.

‘A moment of your time, comes?’ he asked the Half-elf woman. Grea raised her emerald eyes to meet Duro’s gaze and gave him her typical half-smile, nodding. He was always shocked by how pretty his boss was. It was hard to imagine that she was at least twice his age, looking no more than twenty, the age of Duro himself.

‘Everything alright, Duro, dear?’ she asked him, immediately sensing his anger, no matter how desperately he was trying to mask it. Her face was worried, her large eyes peering at him from under locks of flame red hair. The haircut was boyish, yet revealed her slender, feminine neck with the tribal tattoos. ‘You look like you saw the Last Pilgrimage.’

‘I… just… I’m pretty tired, that’s all. But that’s not why I’m here.’ Duro was calmer now. He cleared his throat. ‘One of the Ifreanni might want to nest soon. Vikujambi’s. Too early to say, but she is starting to do the dance.’ he hesitated a little, then added. ‘Very early state, might not lay in the end. Thought you might want to know.’

It was not entirely truthful, of course. Vikujambi’s mount was in full heat, unnoticed by her rider and by whichever handler was responsible for her care. But Duro only wanted to see who reacted to his news, which he said loud enough so that all the gathered beastmasters heard. He deliberately softened up the story to avoid Grea punishing anyone he liked. But from the way Ordis looked up and frowned, he was certain about the identity of the culprit. Duro was not surprised. Since the unfortunate accident of his brother, Ordis was even more careless and bad tempered than usual.

‘Thank you for letting me know.’ the Half-elf woman bowed her head, her gaze betraying only a smidgen of suspicion - it was a bit unusual how Duro approached her about this whole matter. However, he still did not intend to tell on his fellow handler. He had to think it through, because no amount of punishment seemed to bring Ordis’ attitude around, and with the dangers of their long trek, it might not be worth it to turn him in. Duro tended to lean towards more diplomatic solutions, if circumstances allowed. So he just nodded at Grea and left, not failing to notice how Ordis was following him with his sullen stare.

***

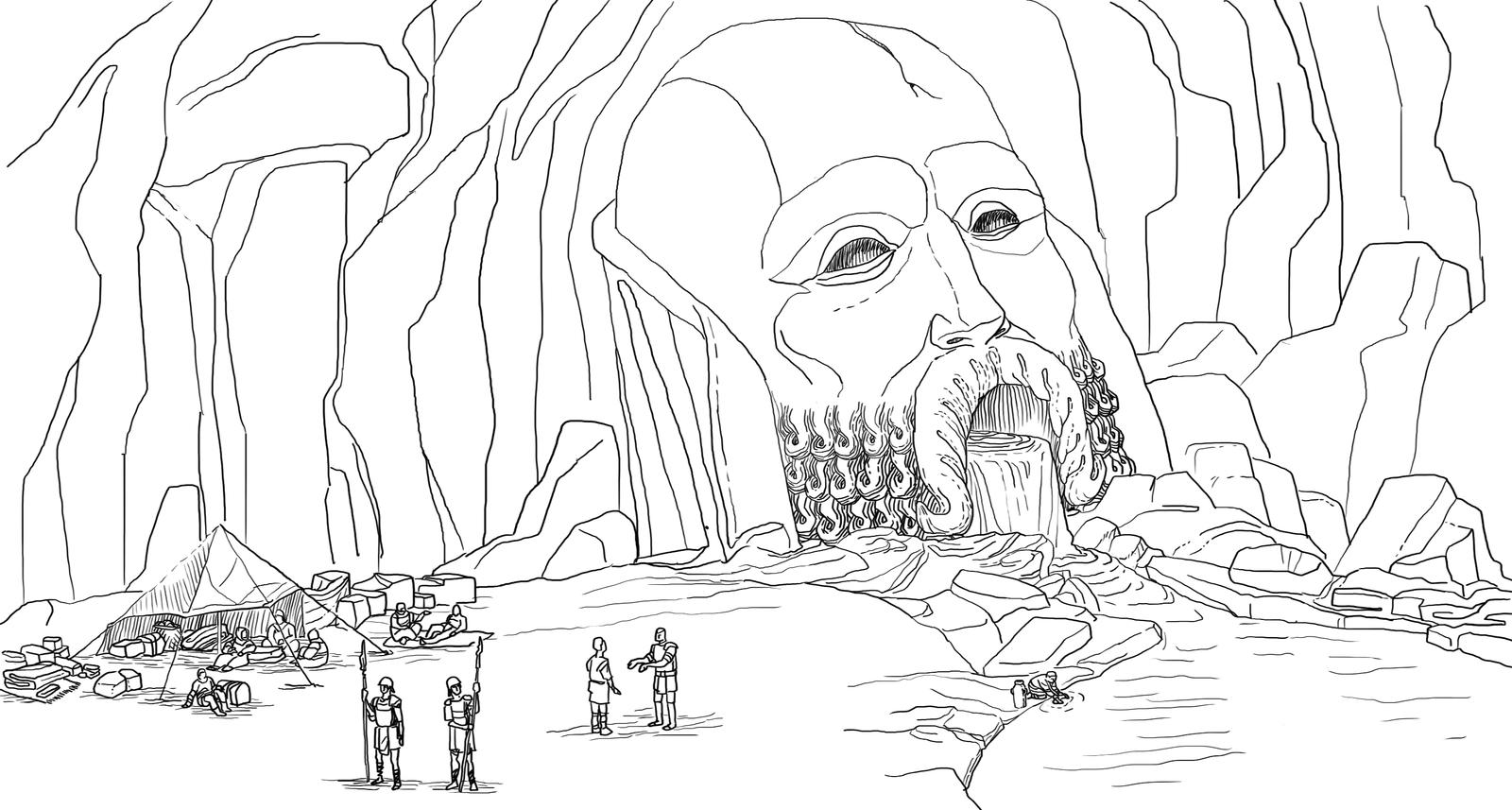

As Duro was making his way towards the far end of the cavern, he started to feel a strange sensation at the back of his neck - as if someone was watching him. He slowed down and looked around. Their camp was stretched out along the huge natural cavern. There was room enough for another comitatus similar in size, but this night there was no one to share their shelter with, except for some lonely travelers who now huddled around their own fires. To the South, the large mouth of the cave yawned, the outside world lost in the darkness of the early night. Only a distant, howling wind and the ache in his legs and shoulders reminded Duro of the hardships of the road that led them here. Tents and campfires were set up along the Western cavern wall, with the beast ward occupying a smaller, albeit still huge, side cave opening from the main hall. Their carts were set up to provide protection from the draught and to serve as a defensive barrier in case of an attack. The more valuable cargo was kept towards the inside of the cave, where a gigantic statue head rested beneath a roof lost in darkness. The fountain that opened from the vast mouth still provided a powerful stream of clear water after more than a thousand years, no doubt thanks to its caretakers who dwelt in the upper rooms of the caves. Indeed, the whole cavern was well-kept and maintained as a comitatus shelter by agents of three allied Trading Houses.

Observing his surroundings, Duro felt the strange tingling sensation at the back of his neck and temples again. He’s been having these since he was a young boy, every now and again. It took him a long time to figure out that the feeling occurred when he was being watched, or somebody thought about him intensely, or even when beasts paid attention to him, which was especially odd. But combined with his natural patience, this talent somehow aided him in understanding animals better, as if he could scry their minds. When near magical phenomena, the symptoms were often accompanied by mild headaches, just like when they crossed the Nanktu Dunes a few days ago and the unmaker storms struck. Affected, the old man called it. Duro remembered how the decrepit quack examined him when he was but a boy, and immediately offered a silver bross for him. Looking back at it, the gleam in the old fossil’s eye suggested he was not interested in young Duro solely professionally. He wasn’t sold then, but neither has he learned much about his talent ever since; barring him adapting to it so that now it came to him naturally and fairly effortlessly. Many inhabitants of the forsaken continent of Xeryn were affected in similar ways - one of the strange residues of the Calamity, no doubt.

The young handler finally located the reason for his strange perception: the slave boy Aru was standing half-hidden in shadows at a stone’s throw from him, leaning on a tent pole, holding a jug that was much too large for his weight and strength. Even though he tore his gaze from Duro right away, the handler knew that it was the boy who triggered his awareness. He smiled and whistled softly at Aru.

‘No need to fret. Come now, parvus.’ he said. The boy hesitated a little, then - hauling the large earthenware jug - walked up to Duro.

‘Where are you headed?’ he asked. The boy indicated the god statue with his chin.

‘To the fountain.’ the word sounded strange from Aru’s lips, the intonation all wrong, as if he has said it for the first time. The handler knew that the slave boy was still learning the Imperial Common Speech, or Imperium Standardis, and indeed, the pace with which he developed was admirable. Yet, his pronunciation was still a bit off. ‘Fetching water.’

‘I was headed there myself to wash up. Mind if I join?’

‘Nah.’ Aru struggled with the large jug, so Duro helped him balance it carefully. They started walking. The handler could not take his eye off the earthenware as it swayed calamitously. He had to stop himself from taking it from the panting Aru - that would doubtless incur the wrath of the slave-masters; yet anger swelled up inside him almost irrationally. Eventually, Aru broke the silence.

‘When the Seket… erm… vagrus said the comitatus uhm...‘ the boy pronounced the word oddly. ‘That it was family. What did she mean?’

‘Well, Sekethma considers everyone in her company like a brother or sister.’ When he saw that the boy was thinking hard, he added: ‘Out here you need to be able to depend on your companions. She wants everyone to understand that there’s no place amongst us for someone who wouldn’t stand by their fellows, but also that we accept anyone who is willing to belong.’

‘Even Ordis?’ Aru asked.

‘Yes, even him.’ Duro’s tone was less convincing now. He was parroting Sekethma’s words without truly believing them - at least in relation to Ordis.

‘But he doesn’t act like family. He growls like a wounded bozka at others, not just slaves. And he threatens others, not just slaves.’

‘True, but you’ve known him only for a few weeks. He’s having a hard time now-’

‘Because his brother died. Yes.’ Aru grunted as he shifted his grip on the jug. ‘But if the comitatus is also his uhm… brothers, why does he hate them? Do they not stand by him, or does he not want to belong?’

Duro was flabbergasted. He did not know what to say, or how to react to such uncompromising clarity coming from a boy who was no more than nine or ten winters old. So he did what most adults do in time immemorial when faced with similar questions: he kept his mouth shut.

They slowly made it to the statue that looked down on them with hollow eyes. The great head was over twenty yards tall, and tipped somewhat to one side. Its bald pate was cracked, and clear water gushed from its wide open mouth. Duro wondered if the frowning face and bulky head continued in a gigantic, buried stone body beneath their feet; if long ago this giant stood high and mighty above ground, looking over a vast, fertile stretch of land.

The skinny boy heaved the clay jug onto the brim of the large basin below the statue head. Duro could no longer just watch, so he helped Aru fill the jug and set it down next to the fountain. Several other slaves who were also fetching water turned a blind eye. Most of them did not belong to the comitatus anyway. The boy was preparing himself for the long haul back. He ran his fingers through his shaggy mane of dark blonde hair and washed his sweaty face. Now that Duro was observing him closely, Aru looked exhausted, a little sick perhaps?

‘Did you know that I used to be a slave, too?’ the handler had no idea why he shared that. The slave boy looked up with a curious expression.

‘And you aren’t now.’

‘No, I was liberated when I was your age.’

‘Sekethma liberated you?’

‘She didn’t, no.’ Duro chuckled. ‘I did not know her back then, this was a long time ago. And Sekethma did not have her comitatus back then. But she is the kind of vagrus who’d liberate a slave for thinking highly of them.’

Aru wore his customary solemn expression as he was scanning the tents and campfires. Duro put a hand lightly on the boy's shoulder.

‘So, I know times are a bit harder for you now, but you’ve got to keep your chin up. Persevere. Being a slave… well, being a slave in this company is not the end of the world.’

***

A long time after Aru had left, Duro was still sitting on the brim of the fountain’s basin, lost in thought, unsure if he himself believed a single word of the advice he gave to the boy. At length, he looked up and noticed that apart from himself and an old slave, no one else was around the fountain anymore. It was getting late, so the travelers who hadn’t called it a day were sitting around their campfires. Booze was being passed around. Stories were being told. Leftovers were being chewed on. Yawns were being stifled. Duro’s gaze stumbled upon the thick-set old slave woman who was filling some clay jars with water. The filled jars were resting in a basket on a flat-top stone nearby, so she was walking back and forth, one jar at a time, wobbling from one leg to the other the way so many elderly women do. He stood up slowly and looked back at the god's head, feeling really small.

‘One always wonders if it continues underground.’ the old woman’s voice woke Duro from his reverie. He turned towards her with a blank expression.

‘Forgive me, dominus. I did not mean to…’ her voice trailed off as she stopped dead and bowed her head in a well-practiced fashion.

‘No, no. It’s all right. I was just lost in thought is all.’ Duro said quickly. ‘I mean no harm.’

‘I wasn’t - ’ she said while stepping up to the basin and filling another jar. ‘ - wrong after all. Your heart is kind, young dominus. The way you treated the boy, I mean. I can see such things, yes, oh I can.’

‘Yet, I could easily be kind to the boy for selfish reasons only. You know nothing about me.’

‘I don’t think so. I saw you help the boy, but I also saw you lost in thought, as you say. Pondering our fate… and yours, if you forgive my saying so. Besides, slaves do not have the luxury to only superficially observe someone and come to a wrong conclusion. And I’ve been a slave all my life, dominus. I am rarely wrong. Among the few boons of old age, I suppose.’ she smiled a predominantly toothless, but kindly smile.

Duro frowned and looked at his feet.

‘I also know that you don’t like to be praised.’ she added, finishing her work with the jars.

‘I’m not looking for avowal when I help someone, if that’s what you mean. No one should.’ he looked at her for a few moments, then finally smiled. ‘You seem to know an awful lot. So does it? Continue underground?’

Her deep-set eyes lit up with fascination when she finally understood. Wrinkles shifted wildly on her ancient face as she started to gesticulate vehemently at the stone head.

‘It most certainly does, dominus! There were some excavations. Curious men took it upon themselves to find out what lies beneath the head. They dug all kinds of holes and tunnels only to find out that the statue continues down and down and down. But they soon gave up and never dug deep enough to reach its pedestal. The knowledge that there is a whole statue buried here under rock and sand satisfied their curiosity, apparently. The fountain was not here back then, mind you.’ she indicated the basin and the flowing water from the god's head. Indeed, upon closer inspection one could see how the sides of the mouth and the jaw were crudely chiseled compared to the rest.

‘These same men found water below, see, and with arduous work they made the water come up and through the head, built the basin and the fountain…’ she trailed off while running her spotted, gnarled fingers through the clear water. ‘Being the clever men they were, they soon sold the rights to the water, the fountain, and even the cave to Trading Houses, making a tidy profit, no doubt.’

‘I wonder if there’s a moral to this story.’ Duro said, now standing next to the old woman.

‘You can probably make up all kinds, really. Maybe that sometimes men who think of themselves as explorers and pioneers end up becoming entrepreneurs and peddlers instead; the reasons they ventured out for, what they took risks for, are much less noble than they think. Or that not all treasure is metal or ancient artifacts. Or perhaps that beneath every dead god’s corpse there may be something that still lives.’

‘You’re quite the philosopher. Do you also know what god this used to be?’ Duro pointed up at the face carved out of hard rock.

‘Unfortunately, there is no solid evidence. Texts written by the first explorers of the caves speak of him, as well as transcripts of ancient writings that used to cover the walls, long gone by now. Both these would indicate that this was one of the Elder Gods who supposedly created the world, or perhaps one of their proxies, a demigod of sorts. Which one? Impossible to say.’

‘It is so difficult to imagine what they were like. When they were still here, I mean. What happened to them? Where did they go? Why have they forsaken the world?’

The old woman pondered these questions a little before answering a bit carefully.

‘You surely know what the Triumvirate of the Empire’s gods and the teachings of the Church say, dominus. The Elder Gods, in their jealousy and resentment towards mankind turned on the Old Empire, descended from Mount Xyn, and caused the Calamity. Afterwards, when they saw what they di-’

‘Yes, yes, but does that not strike you as odd?’ Duro cut her off, tired of the religious drivel he had heard a thousand times before. ‘They felt guilty after incinerating and cursing the continent and the Empire, so they stomped off like angry children?! And we learned nothing of them in the last millennium? I find this very difficult to fathom.’

‘Indeed, it is strange. But what do we know of the gods? Of how they perceive? Of what they really are. We see only what we make them out to be.’ the old woman paused briefly, then bowed her head. ‘But I do agree that Imperial tradition is rather vague and difficult to interpret when it comes to the Calamity and the gods. When I was a young lass, I read replicas of very old texts that talked about the Pact of the Elder Gods; these stipulated that in the First Age, the gods vowed never to set foot in the worlds of the mortals ever again, or otherwise directly interfere with them. That alone would contradict what we think we know about the Calamity today.’

They stood there, looking up and into the empty eyes of the dead god. Duro shivered a little before turning to the small woman, raising an eyebrow in surprise.

‘You read all this?’

‘Yes, dominus. Just because I’m a slave and have been a slave all my life does not mean I’m unlettered.’ she smiled her kindly smile. ‘I used to be a household slave, a teacher for patricians’ children… many, many years ago in Hadrinium. So long ago that it seems like another life now.’ she chuckled to herself and leaned at the side of the flat rock where her basket rested. She looked older and more exhausted somehow. ‘Have you ever been to Hadrinium, dominus? The slopes there at the foot of Mount Xyn have terraces and hills where wheat still grows. The sun is less severe there, and when its light caresses the slopes, crops thrive. Of course, exposed to the harsh storms, magical fallout, orc raiders, and other peril, most of the time the crops are only saved by irrigating them with slave blood. I used to work on those fields as a little girl. Then, because they thought I was clever and because I looked after other children, they trained me to become a teacher. Those were the best days, truly. Until I was sold. My master lost his fortune betting on gladiators, so we were given away as quickly as possible. I got here. No one to teach, really, except for other caretakers sometimes. But it isn’t too bad here, either. Especially now that I’m old as dirt and therefore avoid a certain kind of attention from traveling men. One works and watches the days go by.’

Duro’s heart sunk. He thought of Aru and a life of inescapable servitude. Of masters gambling with the lives of their slaves. Of relentless abuse. The old woman must have seen it in his eyes, too.

‘Now, now, don’t you mind my blathering, dominus. I’m always flapping my gums, I do, but one such as you shouldn’t-’

‘Comes!’ the shout came from a little ways off. Although the person called him ‘companion’, the vitriol in his voice was almost toxic. Duro spun around only to see Ordis and two guards walking towards the basin, only now recognizing the tingling in the back of his neck. The older handler opened his arms as a mock token of friendship while wearing a nasty sneer. One of the guards was Vikujambi, a tall panther of a man, skin dark as night, tossing his impressive dreadlocks casually behind his back with one hand while carrying a javelin in the other. The pelt of a striped mokoru hung on his shoulders. The other guard was Actos, one of Ran’Garr’s sidekicks, an important man in the comitatus. He had a shaggy, unkempt beard and eyes that seemed to smile at all times. He held his hard leather shield over his shoulder while his bronze gladius rested in its scabbard.

‘Look here, boys! The slave-lover’s at it again. He’s not satisfied by seedy little boys alone, so he has to get the ancient sluts as well.’ Ordis turned to Vikujambi and they cackled darkly.

Rage was already mounting inside Duro, but the presence of Actos made him cautious. Ordis did not stop at that, however.

‘And he talks crap about his comes, too! He loves his slaves so much that he forgets who he should be looking after. How’s that right?’

‘Not right at-all.’ Vikujambi chimed in, his voice the deepest melodic rumble. He flashed a blindingly white smile.

The old woman took up her basket with the flasks and with a quick, guilty look at Duro, was already in the process of leaving as quietly as possible.

‘Yeah, go and break wind elsewhere, you shriveled cunt!’ Ordis called after her. Vikujambi leaned down, picked up a stone and threw it at the woman, hitting her on her wide buttocks. Though it was meant to be a soft throw, the Dajmahan warrior’s strength was enough to make a nasty thud, clearly causing great pain; but the slave woman wobbled away in complete silence.

Duro was already mid-movement when Actos stepped between him and Vikujambi, holding out a hand.

‘Don’t be stupid, kid.’ though the eyes smiled, the voice was dead cold.

‘No, ntugu, by all-means, let ‘im be stupid.’ said Vikujambi, still smiling, holding the javelin threateningly at Duro.

‘Go easy, Viku, we just came to talk. To set things right by being reasonable. Smooth it all over. Isn’t that true, Ordis?’

‘We came to say that you might wanna think about who you slander, who you go up against, slave-lover.’ the handler snarled as he stepped closer, but Acton made sure he was still between his comrades and Duro.

‘And you might want to think about your job and how to properly do it. I just saved you from much bigger trouble, Ordis. Do you think Sekethma would still tolerate your ass around here after one of the Ifreanni bit someone’s head off because of your neglect?’ the lad was seething with rage now so much that Vikujambi’s smile and Ordis’s cockiness all but evaporated.

‘And you - ’ he looked at the Dajmahan over Actos’s shoulder. ‘ - know well enough when to report on your mount’s behavior. Don’t believe for a minute that the vagrus would turn a blind eye to that mistake, either. I helped you out both without turning you in. I thought you were clever enough to get the message. Instead, you come here to threaten me?’

After a moment’s strained silence when Duro thought Actos would stab him, Vikujambi turned away and swore in his native Dajmahan tongue. Ordis ground his teeth and was about to say something, red faced, when the guardsman held his hand up to silence everyone.

‘I believe...’ he began. ‘That all of us should simply find it in our hearts to forgive and forget. We should all be minding our own business from now on.’ the smiling eyes were back again when he turned to Ordis. ‘And concentrate on our jobs.’

‘But to be clear, if this goes on…’ Actos turned back to Duro, stepped closer and leaned in so that the young handler could smell the sour root wine on his breath. ‘The easiest thing to make it stop would be to cut out a single troublemaker.’

With that, Actos grabbed Ordis’s shoulder, nodded towards the camp to Vikujambi, and the three of them were off. The older handler kept looking back, promising with a silent, mean gaze that this was far from over. Duro finally noticed that his knees were shaking.

***

Duro made his way quietly, but swiftly between the carts and tents until, turning a corner, he arrived at Sekethma’s large, dark crimson tent. A single guard was sitting in front of the entrance, leaning on his bone-tipped spear sleepily. Before he could react, the young handler was inside.

‘...to that end I think we should also put together a second team, just in case the first needs extraction from the ruins. That alo-’ the vagrus stopped abruptly after she followed her gathered lieutenants’ gaze and saw that Duro was standing at the portal.

Ran’Garr groaned, stood up from his chair, and started towards the lad with a no-nonsense expression on his savage face. Before he could throw Duro out, the vagrus stopped him.

‘What’s wrong, dear?’ her voice was soothing, but worried.

But just as young Duro was about to report the threats he received a few minutes ago, another man burst in, followed by the now wide-awake and protesting guard. This one was one of the slave-masters, a pot-bellied, strongly-built man with a bald head. He was sweating profusely.

‘Vagrus Sekethma…’ he blurted in a terrified voice. ‘One of the slaves is sick. All sort of boils and wounds opened on him in an instant. Just now! Everyone’s terrified. What do we do?’

Their leader wasted no time. Beckoning Ran’Garr, she stormed outside, dragging the slave-master with them. Duro was dumbstruck for a few moments before a terrible feeling seized his heart, and he stumbled out after them.

‘Which slave?’ he called after the group. ‘Who’s sick?’

The man hopped along Sekethma as he shouted back.

‘It’s that skinny new boy, wosshisname… Aru.’

Steam | GoG | Discord | Patreon | Youtube | Twitter | Facebook | Instagram